|

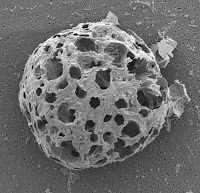

| A scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of an SCP. Their morphology, shape, and colour are completely distinctive (Source: Rose 2015) |

A recent study by Neil Rose (2015) represents a culmination of over two decades of research undertaken at UCL's Environmental Change Research Centre (ECRC). Rose (2015) looks at sediment cores from 71 lakes across the globe, comparing the timing and accumulation of fly ash SCPs from atmospheric deposition. Though observed start dates for the appearance of SCPs in records varies around the mid-19th century, a considerable increase is detectable in all the lakes around 1950 (Rose 2015). The increased deposition of SCPs represents the sharp rise in energy demand from post-WWII introductions of cheap fossil fuels (Rose 2015). Though deposition has generally declined in recent decades for various reasons such as cleaner fuel technologies, less heavy industry, and cleaner air legislation, the mid-20th century peak is a robust and clear signal of human impact.

|

| Figure from Rose (2015), showing the SCP sediment profile from different lakes across the world. Solid black lines are the mean data, and the red bar is the mid-20th century mark (~1950). The rapid increase in SCPs after 1950 are clearly globally synchronous. |

Other indicators of a mid-20th century Anthropocene start, such as trace metals, are prone to degradation and alteration to concentrations from changes in weathering over time (Rose 2015). A popular suggestion is the use of radionuclide fallout from nuclear weapons testing (Zalasiewicz et al 2015), however as Rose (2015) points out, half-lives of these radionuclides prevent them from being a long-term stratigraphic signal. SCPs, on the other hand, have no half-life and thus are expected to preserve well in the long-term (Rose 2015). Furthermore, SCPs are a robust signal at the same time of the Great Acceleration and are temporally close to the Alamagordo nuclear testing of 1945, unlike some proposed radionuclide fallout peaks of the early 1960s (Lewis and Maslin 2015), which occur nearly 20 years after the nuclear testing and a decade after the SCP record peak. As argued by Swindles et al (2015), radionuclides and anthropogenic soil horizons (Certini and Scalenghe 2011) fall out of favour as markers because signals can be diachronous and globally inconsistent.

Thoughts...

Though Rose's study is a fantastic piece of research into a potential marker, and illuminates the permanence of human impact in sediment records, more evidence is required from other natural archives (ice cores, peat, and marine sediments) to confirm the globally synchronous signal. It is essential that the AWG come to an agreement on a suitable GSSP or GSSA for the Anthropocene epoch's lower boundary. SCPs, with their globally synchronous, robust and crystal-clear anthropogenic signal, could be just what the group has been searching for to define the onset of the Anthropocene.